The feeling of being “uncertain, anxious and vulnerable” defines a creeping health insecurity problem riddling parts of the U.S. patient population—demographics who are underserved and at higher risk of outcomes such as amputation. And they can be a barrier to obtaining healthcare, according to Rana Afifi, MD, an associate professor of vascular surgery at McGovern Medical School, University of Texas Health Houston. Afifi was speaking during an invited presentation on strategies that can be used to tackle health insecurities during the 2023 Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery (SCVS) Annual Symposium in Miami (March 25–29).

“There [are] plenty of data in the literature [showing] that there is a significant increase in the number of publications that show the relationship between social determinants of health and outcomes,” she told attendees. “However, what is lacking is the data regarding how we do any strategies to improve, implement or actually have any intervention…”

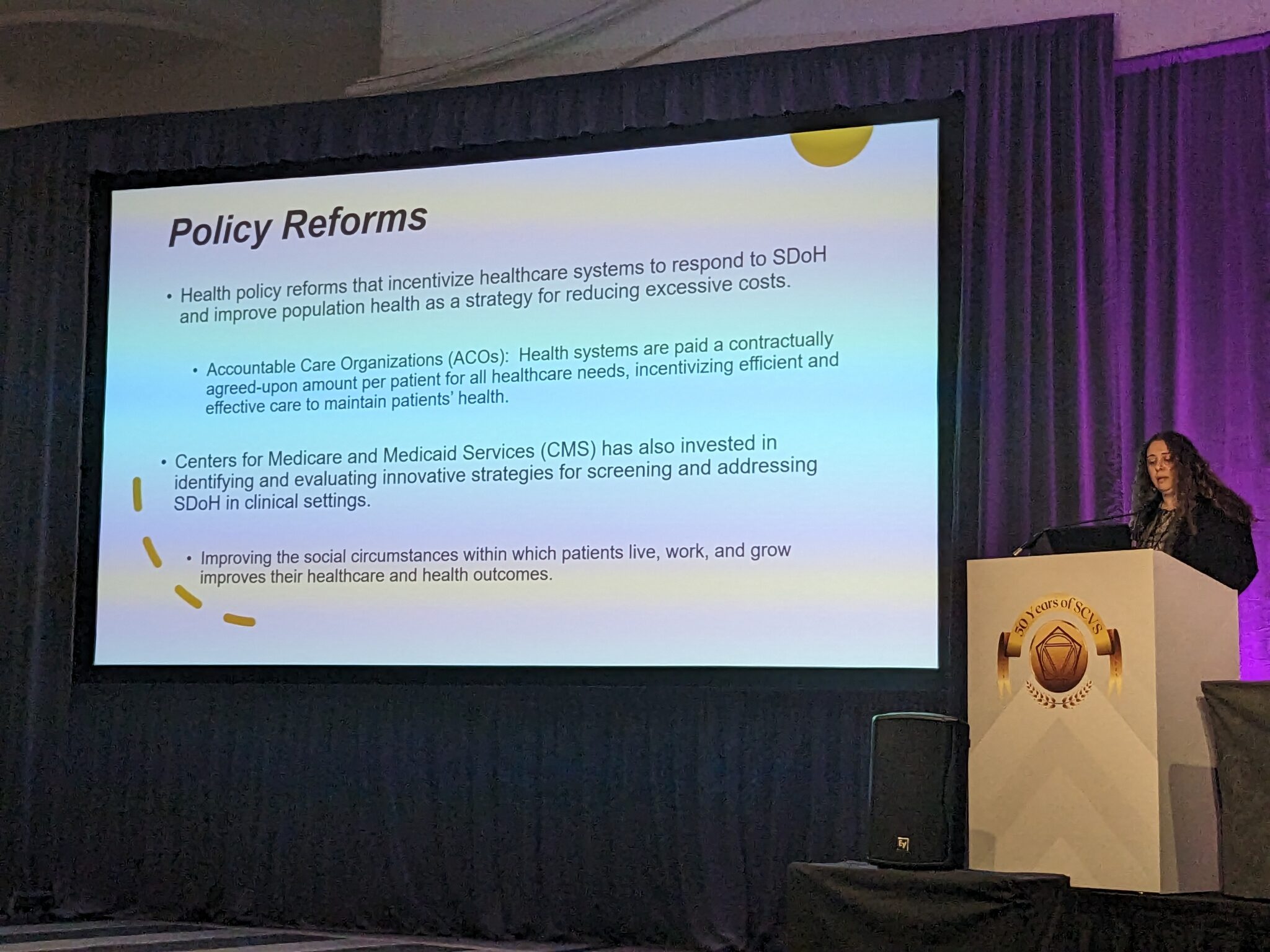

Afifi spoke of health policy reforms that “incentivize healthcare systems to respond to social determinants of health and improve population health as a strategy for reducing excessive costs.” She also focused on strategies already available that can be applied locally. Afifi dealt with health security issues as they relate to such areas of life as housing, finance, transportation and food. “You can work with food banks,” Afifi said. “There have been studies showing their role in care for patients and mitigating some of the health insecurities at risk for this.”

She turned to the example of the SAVE (San Antonio Vascular and Endovascular) Clinic in San Antonio, Texas, founded and run by vascular surgeon Lyssa Ochoa, MD, as a case in point. Ochoa based her work on identifying the zones where, for example, there are high amputation rates and low socioeconomic status—high-risk populations, observed Afifi. “That’s basically where she based her outreach clinics,” she said. Her network is equipped with vascular care-equipped mobile units that head out into the heart of these communities, “assisting with some of the transportation options.”

Ochoa and her team also partner with community healthcare workers to navigate wider needs, such as screening and trust-building. Going forward, the health insecurity issue necessitates a cultural change, and needs to be addressed at multiple levels, Afifi added. “The way to address it is from the top down and the bottom up at the same time—we can’t just wait for policy to change.”