On Oct. 28, 2020, the University of Vermont Health Network—consisting of six hospitals in Vermont and upstate New York, was hit by a cyberattack.1 Leading up to the attack—the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) released a warning regarding ransomware targeting healthcare facilities across the country.2 On Twitter, CISA stated “there is an imminent and increased cybercrime threat to U.S. hospitals and healthcare providers.” The FBI and the Department of Health and Human Services warned of credible information about an imminent cybercrime affecting at least five hospitals that could affect hundreds more.3,4

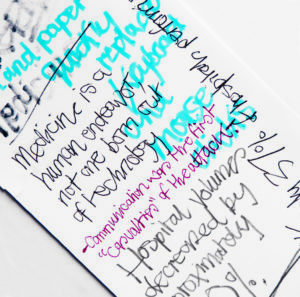

This technological invasion was the result of a malware scheme that affected the information technology infrastructure and significantly curtailed our processes of care including the Epic-based electronic medical record (EMR), picture archiving and communication system (PACS), Outlook email, network computers and printers. Providers at all levels were quickly thrust back into the “paper age” of medicine and scrambled to adapt. Simple activities such as note writing, ordering, and reviewing laboratory values and images were thrown into disarray. Pen and paper quickly replaced keyboard and mouse clicks.

In response, hospital volumes decreased by approximately 20%. Trauma patients were diverted, and elective imaging such as cancer surveillance and screenings were postponed. The surgery department reviewed scheduled operations daily and was able to maintain the operating room at 60–70% capacity. Hands on human checks became paramount as day-of-surgery admissions were limited, staggered starts were implemented, and turnover was prolonged.

VASCULAR LIMITS

The vascular division responded by limiting procedures to those deemed necessary and doable in this environment. Similar to the early days of the pandemic, our ability to triage cases became paramount. After evaluating the systems capabilities, we decided to divert ruptured aneurysms, except for those presenting to our main hospital emergency room. Complex procedures were postponed out of concern for our ability to promptly respond to any intraoperative or postoperative complications.

Our dependence on the catalog of PACS images was a liability for vascular surgery and other services such as neurosurgery and orthopedics. With prior computed tomography angiography (CTA) and arteriograms, unavailable surgeons were forced to weigh the merits of delaying scheduled procedures or repeating images. In response, workstations manned by live radiologists were stood up for review of new imaging, and compact discs, a 1980s technology, became a necessity. The convenience and efficacy of reviewing internal and external images from the clinic, office or home was lost.

COMMUNICATION BREAKDOWN

Communication was one of the first “casualties” of the attack. With network email and intranet access inoperable, hospital, departmental, and division leaders and program directors were challenged to inform employees, residents and fellows about the evolving situation. Frequent conference calls, Zoom meetings and word of mouth replaced other means of communication. Many services resorted to text messaging and WhatsApp for non-patient related communications.

Face-to-face sign-in and sign-out meetings took on added importance. The vascular team resorted to a “war room” atmosphere, with a white board to track patient location and clinical progress. The inability to review the medical histories was partly mitigated by converting to the Vermont Information Technology Leaders (VITL) Access, which allowed providers limited review of recent notes and reports.5 Two weeks into the cyberattack, a read-only version of Epic was brought online—greatly assisting clinicians. This EMR was eerily frozen in time, but was functional enough to inform providers about patient histories, medications, lab and radiology reports.

The current generation of medical students, residents and fellows have “grown up” in a paperless work environment. Many had never handwritten a prescription, or been trained in the proper documentation for handwritten notes. Hard stops and safety measures ingrained in the medical record were rendered ineffectual. It is clear that our house staff, advanced care practitioners, pharmacists, laboratory staff and nurses shouldered the largest burden and stress during this time. The Graduate Medical Education Office held regular Zoom calls to discuss and respond to our trainees’ needs. Teaching conferences—already virtual—temporarily focused on how to effectively support our residents and fellows.

PREPARATION

Relatively speaking, healthcare systems are behind other industries in cybersecurity. Understandably, they have focused more on data privacy than data security. According to one report, only 37% of hospitals perform annual cyberattack response exercises.6 We hope that our experience will educate others about their own vulnerabilities and act as an impetus for hospital leadership to prepare contingencies.

Awareness and prevention are a key component. Up to one in seven hospital employees have opened phishing emails, it has been reported.7 While the ability of any one surgeon, division or department to prepare is limited, individuals acting collectively can make the most of a bad situation. For example, simple backup measures—such as the physical availability of paper forms and prescription pads, despite the hospital going electronic years ago—were indispensable.

It will be necessary and important to retrospectively examine the impact of cyberattacks on patient care. While no serious events have been reported, previous attacks on healthcare facilities have impeded care, and, in one high profile case in Germany, led to the death of a patient owing to a delay in transfer to the appropriate facility.8 At a minimum, cyberattacks can be of substantial financial consequence, as illustrated by the WannaCry attack on the U.K.’s National Health Service.9,10

Other issues like the potential impact on wireless vital sign monitors and medical devices should he considered. Fortunately, at the time of this writing, the coronavirus pandemic was under reasonable control in the state of Vermont, and the University of Vermont Medical Center COVID-19 volume was low.

There may well be unintended consequences of the cyberattack, including a new appreciation for the oft-maligned EMR, and a greater sense of community within the hospital arising from a shared experience. Countless individuals rose to the challenge in a cooperative, constructive manner. They adapted to the situation in the best interest of their patients and colleagues, proving once again that medicine is a human endeavor—not one born out of technology.

REFERENCES

- https://www.uvmhealth.org/medcenter/news/cyberattack-statement-uvm-health-network-president-and-ceo-john-brumsted-md

- Ransomware Activity Targeting the Healthcare and Public Health Sector. https://us-cert.cisa.gov/ncas/alerts/aa20-302a Accessed Nov. 13, 2020.

- https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/28/politics/hospitals-targeted-ransomware-attacks/index.html

- https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/28/us/hospitals-cyberattacks-coronavirus.html

- https://www.vitl.net

- Cybersecurity in Hospitals: A Systematic, Organizational Perspective. Jalali M.S., Kaiser JP. J Med Internet Res. 2018 May 28;20(5):e10059. doi: 10.2196/10059.PMID: 29807882

- Assessment of Employee Susceptibility to Phishing Attacks at U.S. Health Care Institutions. Gordon W.J., Wright A., Aiyagari R., Corbo L., Glynn R.J., Kadakia J., Kufahl J., Mazzone C., Noga J., Parkulo M., Sanford B., Scheib P., Landman A.B. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1;2(3):e190393. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0393.PMID: 30848810

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/sep/18/prosecutors-open-homicide-case-after-cyber-attack-on-german-hospital

- Ghafur, S., Kristensen, S., Honeyford, K. et al. A retrospective impact analysis of the WannaCry cyberattack on the NHS. npj Digit. Med. 2,98 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0161-6

- Cyberattack on Britain’s National Health Service—A Wake-up Call for Modern Medicine. Clarke R., Youngstein T. N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 3;377(5):409-411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1706754. Epub 2017 Jun 7. PMID: 28591519

Daniel Bertges, MD, is associate professor of surgery and medicine and program director of the vascular surgery fellowship at the University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington. Georg Steinthorsson, MD, is the same institution’s chief of vascular surgery. Andy Stanley, MD, is a vascular surgeon and deputy chair of surgery at the University of Vermont and the University of Vermont Medical Center.