SAVVE trial principal investigators discuss results showing 98.4% VenoValve device patency, 85% clinically meaningful benefit and an 80% rate of ulcer size reduction at 12 months.

Fresh from delivering positive one-year data from the Surgical Antireflux Venous Valve Endoprosthesis (SAVVE) pivotal trial at the 2024 VEITHsymposium in New York City (Nov. 19–23), site principal investigators Matthew Smeds, MD, and Raghu Motaganahalli, MD, are both ebullient about what the results might mean about the future for patients with chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) and venous ulcerations.

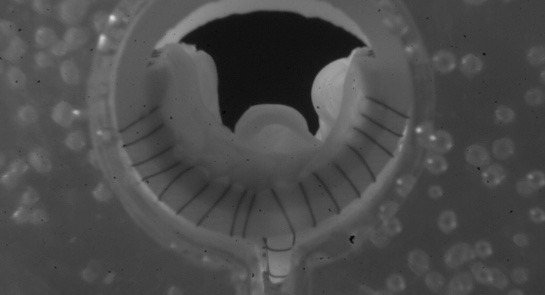

The data show that 85% of patients surgically implanted with a bioprosthetic VenoValve (enVVeno Medical) reached the one-year milestone having achieved a clinically meaningful benefit of a three or more-point improvement in revised Venous Clinical Severity Score (rVCSS); a 7.91 point average improvement in rVCSS; clinically meaningful benefit across all CEAP (Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical and Pathophysiological) classes of patients enrolled (C4b–C6); 97% target vein patency at one year; and significant resolution in venous ulcerations.

“It is the first device we have had to treat deep venous insufficiency in years,” Smeds, a professor of surgery and the former division chief of vascular and endovascular surgery at Saint Louis University in Saint Louis, Missouri, tells Vascular Specialist in an interview in the days after presenting at VEITH 2024. “These patients are typically relegated to compression therapy alone. There are no really great surgical options for this issue.”

Similarly, Motaganahalli describes the novel device as representing a “game-changer” given how previous attempts at developing a surgical option for the CVI patient population failed to take hold. “The procedure does not have a steep learning curve; technically, this is a procedure that can be accomplished by any trained vascular surgeon. It is not technically demanding,” says. “Before, these were technically demanding operations: if you really look at the historical data from internal valvuloplasty or external valvuloplasty, vein valve reconstruction, vein valve transplant—they were effective in a few select centers and a few select hands, but that result was not reproducible at multiple centers.”

Smeds zeroes in on the topline result of 98.4% device patency and considers how there were nine device occlusions over the course of the one-year study. “However, eight of them re-canalized,” he explains. “I had some patients that thrombosed the device. Interestingly, in one of them I sucked out the thrombus via mechanical thrombectomy and then it occluded a few weeks later. I thought that that device was never going to be functional, but, within a month or two, the device recanalized and the patient had decreased reflux below the device and was healing her ulcer.”

Though these thromboses were each marked down as a device “failure,” Smeds continues, the fact eight reopened and many were then functional represented pleasant surprises. “I think you see that in the natural history of people with DVTs [deep vein thromboses] to begin with,” he explains.

Elsewhere among the data, he picks out the trial’s inability to pinpoint a direct relationship between reflux and ulcer healing, and the role of compression therapy compliance as intriguing propositions. “We cannot find a direct one-to-one ratio in terms of if you have a really high decrease in reflux, then you get a really high ulcer healing rate,” Smeds says. “So, there are certainly more complex things going on at a patient-to-patient level with the device as far as who is benefiting from it.

“We also looked at whether there was full compliance for compression therapy—whether that increased or decreased over the length of the trial—and there was a slight decrease in its use, which demonstrates that the device is doing something to aid in the ulcer healing and the symptom improvement, because it wasn’t necessarily due to an increase in compression.”

For Motaganahalli, chief of vascular surgery and program director at Indiana University in Indianapolis, ulceration reduction data were stark. In those who had their ulcers for less than three months, the SAVVE trial demonstrated there was 100% resolution— “complete healing,” he says. “Most of the patients who had an ulcer more than a year or so, even then 60% of them showed full resolution of the ulcer. In terms of the average area of the ulcer—especially in those who had a longer duration of ulcer—those patients had an average ulceration of 20.6cm2 at baseline, and that reduced to 12.3cm2.”

Motaganahalli sees a promising future for the device: “The one-year data tells you that it provides a sustained benefit of symptomatic improvement for patients with CVI. The VenoValve is a safe and effective treatment for patients with CVI due to deep valvular incompetency. It’s not only effective, but effective across the whole spectrum of CEAP classification: for C4b through C5 and C6. The benefits were seen within the first three months and were sustained through the one-year period of observation.”

Motaganahalli also lingered on the significance of the improvement in average rVCSS among the trial cohort: the 7.91 score recorded at 12 months came amid a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandate for a more than 3-point advance in rVCSS. “Here, more than 85% of the patients had more than a 3-point improvement,” Motaganahalli notes.

On the eve of the VEITHsymposium, enVVeno Medical announced it had submitted an application with the FDA seeking approval to market the VenoValve based on the one-year data Smeds and Motaganahalli presented. The company is also developing a next-generation, non-surgical transcatheter-based replacement venous valve called enVVe. It is expected to be ready for its own pivotal trial in the middle of 2025.

Smeds is excited by the portent of what might be to come as development of the devices proceed. The venous system is still “Pandora’s box as far as putting devices and valves in there,” he says. Further, in the SAVVE trial, each patient was implanted with only one replacement valve. Smeds considers the questions of whether more than one device should be fitted in patients to further decrease reflux; whether in patients with duplicate incompetent systems both should receive a VenoValve; and whether the location of the replacement valves should be modified. “There are a lot of unknown questions that will hopefully begin to be answered once this becomes FDA approved,” he adds.

Motaganahalli believes some might query the device cost once it enters the market but sees the potential impact on the heavy cost burden associated with wound care for venous ulcers as a boon. “If you look at the cost of treating ulcerations, several billions of dollars are spent annually,” he says. “With appropriate patient selection, the device can do wonders. We have 2.5 million potential patients with CVI in the U.S., with close to around 40% missing workdays, $3 billion in direct medical costs, $30,000 per patient in terms of the annual cost of ulcer treatment, with the potential for 20–40% of these patients to have a recurrence. This makes the device a very attractive option.”