Welcome to the CLTI Chronicles, a saga of mystery, medicine and misadventures in limb salvage unfolding weekly in my office, where the drama of threatened limbs rivals any Latin telenovela. My clinic has become a crossroads for the second opinion seekers, the exclusive club of the limb-threatened, each bearing the mysterious mark of CLTI—critical or chronic limb-threatening ischemia, who can say?—a definition that looms like a shadow and is as elusive as a politician’s promise.

Imagine this: A parade of patients, each with a medical history reading like a travelogue through the land of “100% successful interventions.” They’ve journeyed through the valleys of endovascular treatments, scaled the mountains of open surgeries, and been guided by a motley crew of vascular magicians and interventionalist du jour. Yet, here they are, in my office, still sporting their troublesome limbs like unwelcome souvenirs from a trip gone wrong. After a forensic dive into their histories, imaging and procedures, the twist emerges—the majority did not have CLTI as their opening act.

But wait, there’s more to this plot. It seems there’s a CLTI epidemic sweeping the nation, and it’s not just confined to the realms of vascular journals or my office; it’s trending on social media as well. You’ve seen the angiograms, those before-and-after images where you can’t help but wonder: “Really? Was that truly CLTI?” It’s a diagnosis in vogue and it appears my community has become the unofficial epicenter of CLTI, defying statistical probabilities where CLTI represents 10% of patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD). But beneath the surface lies a narrative steeped in gravity: amputation risk as high at 40% in six months and an all-cause mortality rate of 70% in five years that overshadow colorectal cancer, breast cancer, stroke and coronary artery disease. CLTI is not just a hashtag; it’s a killer outshining the darkest plots of a Stephen King novel.

Then came that moment of reckoning. A patient asked me an innocent question: “What is CLTI?” I was dumbstruck, my mind a vortex of nothingness. Eventually, I managed to mutter something about the looming threat of limb loss, avoiding the gory details of wounds, arterial blockages, and the like. That encounter sparked in me a quest through the vascular literature and the abundance of expert forums including SVSConnect, searching for that Holy Grail: a definition of CLTI. A definition that would be as easy to recite as ordering an iced latte at Starbucks. What I uncovered was a labyrinth of conflicting viewpoints, a chaotic battleground of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and ambulatory surgery centers, along with squabbles over interventional integrity, all leaving me still craving that elusive clarity. By the end, I found myself more tangled than a season finale of the Bachelorette.

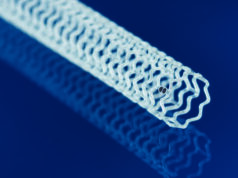

In the world of vascular disease, we have a lexicon to define just about everything, except, it seems, for CLTI. It’s like trying to nail jelly to the wall. Guideline-directed therapies? Sure, we’ve got those—a veritable buffet of evidence-based options, from interventional routines, to limb salvage approach, to cardiovascular risk reduction. But where’s the meat of the matter? My commentary is not about the mechanics of arterial repair (stents, balloons and atherectomies), but about the missing clarity in the definition, a gap leading to fragmented and variable care for our characters in distress, turning CLTI recommendations into a kind of medical choose-your-own-adventure.

The backstory takes us to the 1980s European effort to define not just questionable fashion but this elusive antagonist, focusing on rest pain, tissue loss and hemodynamic parameters. But like all great plots, it’s riddled with twists— subsequent studies showed a broader spectrum of patients with ulcers and normal hemodynamics who benefited from early interventions, despite the initial definitions of CLTI. Fast-forward through decades of academic adventures and classification crusades—from TASC-I followed by TASC-II to the University of Texas classification to PEDIS to the SVS Lower Extremity Threatened Limb Classification better known as WIfI (Wound, ischemia and foot infection)— each a chapter in the never-ending saga of CLTI. Yet, despite all these classifications, the true essence of CLTI remains as elusive.

Then, in a sudden plot twist, 65 years after Fontaine first attempted to classify this process, enter the GLASS investigators, the latest heroes in our tale, attempting to demystify CLTI with a blend of PAD, rest pain, tissue loss present for greater than two weeks, and a sprinkle of hemodynamic intrigue including ABIs, toe pressures and transcutaneous oxygen measurements. But wait, there’s more! Embedded within CLTI are definitions within definitions layering our CLTI mystery novel—PAD, rest pain, gangrene and ulcer, each a sub-plot within the grand narrative of CLTI. Does one have PAD based on anatomy, hemodynamics or symptoms? Many patients with PAD are sedentary (obesity, shortness of breath, lumbar disc disease, diabetic neuropathy, frailty) and do not experience symptoms. What if the patient describes burning, tingling or numbness, is that considered rest pain?

In the latest chapter of the ongoing saga that is CLTI, definitions have taken a dark turn, becoming less about medical precision and more about wielding the grim reaper’s scythe over the heads of our protagonists. It’s as if some Dickensian villain has whispered into the collective ear of the vulnerable, “Beware, an amputation awaits those with rest pain,” turning a choice into a tale of certain dread.

Now enters our reluctant hero, the every-patient, who earns his living from his motor skills and finds himself at a crossroads. Offered the devil’s bargain: a “low-risk” procedure pitched with the same persuasive charm as Clark Stanley, aka the Rattlesnake King, versus the foreboding loss of a limb—a phantom limb, haunting his future. The narrative escalates, becoming a weapon that doesn’t just threaten physical loss but launches a calculated strike at the patient’s dignity and self-worth. The looming threat of amputation casting a long shadow in the corridors of his mind is compounded by the barking of the black dog of depression causing our character to turn to a form of self-flagellation.

“Well, if my leg’s going to be tossed out like bad leftovers, why not call the shots on my way down,” he suggests as the cigarette smoke swirls like the fog in a San Francisco sunrise. Unfortunately, following a “100% successful procedure” and now post amputation, he is only a shadow of his former self—a poignant reminder that our medical decisions are not just clinical; they’re deeply personal. We forget and overlook the human element in return for technical success and financial gain.

The tale of CLTI cannot be told without the pioneers who in the early- to mid-20th century outlined the early principles of vascular occlusive disease and oversaw both clinical and experimental techniques in revascularization. We tip our hats to the trailblazers—Carrel, Leriche, Jaboulay, Kunlin, DeBakey, Dotter and Grüntzig—who, with the verve of pioneers and the audacity of explorers, sketched the early maps of vascular wilderness. Yet, here we are, nearly a century later still caught in the whirlwind of defining and redefining CLTI. Despite the cash tsunami funneled into research and development, we’re somewhat akin to hamsters on a wheel—spirited but spinning in place.

We’ve also now ventured into new territories, from infrapopliteal to inframalleolar, with the same zeal and optimism as a toddler’s first steps—eager, if not a tad wobbly. Over the last century, through the thick tome of literature, with acronyms that could double as the latest tech start-ups, we’ve showcased our unwavering commitment to tackling PAD and limb salvage. But the gold standard? It’s still Kunlin’s single-segment GSV bypass from 1948—vintage, classic, yet undefeated.

And so, I lament, perched upon decades of innovation and introspection: “Have we truly advanced in our quest against CLTI, or are we just marching to the nostalgic rhythm of past triumphs?”

Our final chapter calls for unity—a rallying cry for a collaborative, evidence-based definition of CLTI that stands the test of time and scrutiny. A definition that’s not a mere classification of the severity of a disease process but a clear and concise answer to the question, “What is CLTI?” We can all conclude that CLTI is not localized and segmental, as our interventions suggest. The complexity of CLTI, influenced by a kaleidoscope of patient factors, poses a formidable challenge and we should start to look to the future where advanced molecular, genomic and imaging techniques is what helps define CLTI. After all, rest pain, multi-level occlusions, wounds and hemodynamic derangements are simply downstream consequences of CLTI and we should get away from the circularity of using these constructs to define CLTI.

Perhaps the answer lies in simplicity—a return to the basics, where critical limb threat encompasses not just a focus on what can be intervened upon anatomically, but a larger story about the human element: the people attached to the limbs, their stories, their risk factors and paths through the intricate world of vascular health.

Omid Jazaeri, MD, is a medical director of vascular services at AdventHealth in Denver, Colorado.