This advertorial is sponsored by AOTI.

Two prominent vascular surgeons discuss a rising tide of evidence pointing toward benefits of adjunct use of cyclically pressurized Topical Wound Oxygen (TWO2) therapy in the treatment of vascular ulceration.

The best way to think about modern-day limb salvage, says Anahita Dua, MD, is through the analogy of what would constitute a fully functioning car. Underpinning the chassis, you might have the perfect set of tires, that never puncture, to enable motion, she relates, but without a multitude of other vital components—an operational engine, safe, working seatbelts—the vehicle is going nowhere. Without them, “that is not a car,” Dua explains.

Substitute in limb salvage for the car, and a similar picture emerges, the associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School in Boston and a vascular surgeon at the Massachusetts General Hospital continues. “The approach to limb salvage has historically been very much, ‘What is my silo? I’m a vascular surgeon. I am good with blood flow. I am going to increase your blood flow.’ That’s great, but if someone is not doing good wound care, and someone is not putting you on antibiotics, and you, as the patient, are not stopping smoking, your leg is going to get amputated.”

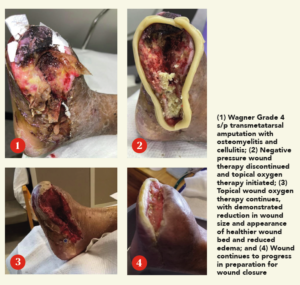

In the case of the car, an operational vehicle is more than the sum of its parts. In the case of limb salvage, the contributions of a multidisciplinary team yield better results than individual specialties operating in isolation. Fitting squarely into the heart of this picture is the role of patient-applied at home TWO2 therapy (AOTI) in aiding ulcer healing following revascularization. Dua points to a classic case to demonstrate how crucial the therapy is to successful wound salvage (see figures 1–4).

“This patient, a 68-year-old male with diabetes and end-stage kidney disease [ESKD], is absolutely someone who would have been amputated, but on whom we carried out a deep-vein arterialization [DVA] procedure, allowing blood flow to get to the foot,” she says. “That process takes time, and, during that time, you don’t want the wound to disintegrate, get infected and the person end up getting amputated. This being a patient with diabetes and ESKD, we are talking about the worst of the worst type of blood vessels. In spite of that, we healed this wound with, of course, great wound care: good blood flow was formed from the DVA, and then came TWO2 therapy.”

“This patient, a 68-year-old male with diabetes and end-stage kidney disease [ESKD], is absolutely someone who would have been amputated, but on whom we carried out a deep-vein arterialization [DVA] procedure, allowing blood flow to get to the foot,” she says. “That process takes time, and, during that time, you don’t want the wound to disintegrate, get infected and the person end up getting amputated. This being a patient with diabetes and ESKD, we are talking about the worst of the worst type of blood vessels. In spite of that, we healed this wound with, of course, great wound care: good blood flow was formed from the DVA, and then came TWO2 therapy.”

David Dexter, MD, an assistant professor of clinical surgery at Eastern Virginia Medical School and a vascular surgeon at Sentara Vascular Specialists in Norfolk, Virginia, sees the role of multimodality TWO2 therapy in a similar way. In the setting of arterial disease, he explains, both macro-and microvascular problems need to be tackled. An array of major technologies exists for the former while therapies for the latter remain in their infancy, Dexter says, but there is also the issue of ischemic skin changes—and these “need to be addressed in order that continued ongoing tissue loss be reversed and healed.”

“We have the ability to revascularize a limb that’s functionally dead, but without the ability to heal the wound after we’ve removed necrotic tissue after we’ve fixed the macrovascular problems, we’re at a loss,” he explains.

That’s where Dexter sees TWO2 performing a crucial role, not only in tackling the totality of the disease process but also in returning patients to normal, everyday life.

“First, I would say it needs to no longer be seen as late-stage therapy to bring wound care adjuncts like TWO2 in,” he continues. “There must be a plan: that when somebody comes in with CLTI [chronic limb-threatening ischemia] and ulceration, or with gangrene that will lead to tissue loss, we say, ‘How do I get this patient back to a functional foot that they can walk on?’ If you have a wound that you’re going to create, do you have the ability to surgically close this wound, or will advanced local, topical therapy assist me in that? Because the longer the wound is open, the longer the patient is off their extremity floor and non-ambulatory, the worse they are going to do from a protoplasmic standpoint.”

Both Dua and Dexter are unequivocal in how TWO2 functions to help heal wounds. Referencing the same case involving the 68-year-old diabetic ESKD patient who underwent DVA and then received TWO2 therapy, Dua tackles the counterargument of the same patient receiving the same treatment plan, minus TWO2.

“What if you did everything that you did, but you didn’t do the cyclical compression oxygen therapy?” she explains. “Would it have made a difference? The studies show that when you randomize patients to two groups, the ones who got TWO2 therapy did better.”

An international randomized controlled trial [RCT], conducted by Robert G. Frykberg, DPM, and colleagues, showed that cyclical pressurized topical oxygen therapy adjunctive to optimal standard of care is significantly superior to standard care alone in healing diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) at 12 weeks and one year.

For Dexter, the venous side, on the other hand, reveals what he describes as the flip side of the coin. “The number is debatable, but 15% of all venous ulcers do not heal, have not healed and likely will not heal, and they become a chronic health problem for these patients,” he says. “They don’t lead to amputation, they are ambulatory, they are at their normal state of health but still have this wound that changes their everyday function and everyday life,” he continues, adding, “that’s where the increased oxygenation uptake of giving local topical hyperbaric oxygen therapy with some moisture directly to a wound comes in. If you can heal half of that 15%, that’s a huge magnitude of patients we have helped.”

Dexter tackles the subject of how oxygen therapy is traditionally viewed: full-body hyperbaric oxygen delivered in dive tanks. “I don’t think any of the skeptics argue with the math,” he says. “There is very clear evidence you can hypersaturate with hyperbaric pressure oxygen and deliver more to wounds both intravascularly and directly through the skin surface. From a cost standpoint, it becomes prohibitively expensive to dive, or pressure chamber, the number of patients we have. We have restricted that resource across the world for three generations. So the reason we don’t have data is it’s impossible to get enough people into trials doing things like this.

“TWO2 therapy allows at-home application for a fraction of the cost, both to the payor and to the patient. We are in a position where we are ready for an appropriately powered randomized controlled trial in venous leg ulcers [VLUs], to support existing published observational cohort studies, looking at wound healing rates and wound healing percentages.”

Fundamentally, says Dua, returning to her earlier argument, the types of wounds in question here are not those that “would have healed anyway.” These are vascular patients who see marked wound healing through the use of TWO2 therapy in the setting of severe vascular disease, she explains.

“If I told you the wound would heal seven days faster than if you didn’t use it, but it costs a million dollars, you’re going to say, ‘You know what, I’m just going to wait the week and heal it.’ Why would I spend a million dollars, right? That’s the whole point about cost effectiveness, but all of those situations are about wounds that are ‘going to heal anyway.’ These wounds I’m talking about would have probably progressed and the patient may have become an amputee.”

The therapy won’t work for every patient, every time, Dua adds. Like the tires on a car, “this is an adjunct, a piece of the puzzle that is going to help you save legs” and obviate wound complications down the road before they get the chance to develop.