There is an incremental increase in the risk of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) among those with a family history of the disorder based on degree of relation—with a significantly higher risk found in patients with a first-degree relative diagnosed with an AAA.

The findings were delivered during a scientific session at the Western Vascular Society virtual annual meeting (Sept. 27—29), covering familial risk of an AAA and the implications for population screening by Claire Griffin, MD, an assistant professor of vascular surgery at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

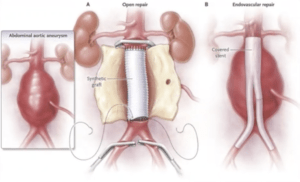

AAAs are the 13th leading cause of death in the U.S., with a prevalence of 4–8%, Griffin observed. Current U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines recommend a one-time abdominal ultrasound to screen for AAAs in men aged 65–75 who have ever smoked, with the main risk factors for AAA being male sex, a history of smoking and family history. However, she pointed out, no screening is recommended for women who have smoked, and there are no specific screening recommendations from the USPSTF for patients with a family history of AAA.

“The USPSTF screening guidelines are adopted by both the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians, both of which do the majority of screening in patients,” she said during her Sept. 28 talk. “The 2009 Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) practice guidelines did recommend screening in patients with a history of AAA in their family but this has not been widely practiced.”

Griffin and colleagues at the University of Utah hypothesized that the Utah Population Database—which she described as a unique resource with extensive family histories, diagnosis records, causes of death, birth and death years and statewide inpatient claims data, allowing for a robust genetic association—could provide “a robust and relative patient cohort to answer the true familial risk of AAA in a low tobacco use environment.”

All patients in the database with a diagnosis of AAA were included and matched with 10 age and sex controls. After exclusions, almost 250,000 cases and their relatives were matched to 2.8 million controls. “A fixed effects model was used including the co-factors of time to diagnosis, type of relative, sex of relative, ethnicity and birth cohorts as non-interacting terms and an interaction model between relative type, age group and sex of relative,” Griffin explained.

The researchers found that the risk of AAA diagnosis increased in an incremental fashion based on degree of relation to the case, with a hazard ration (HR) of 3.02 for first-degree relatives (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.75–3.31; p<0.001), 1.60 for second-degree relatives (95% CI, 1.42-1.72; p<0.001), and 1.33 for first cousins (95% CI, 1.26-1.42; p<0.001).

They also found the age at diagnosis was “noticeably earlier” in the cases and relatives compared to control groups, with a HR of 8.3 (p=0.03) for those aged 0–33 and 4.65 among those aged 55–64 (p<0.001).

Concluding, Griffin told meeting attendees: “There’s a significantly higher risk of AAA in patients with a first-degree relative with a diagnosis of AAA, and age at diagnosis is often younger than current widespread screening guidelines recommend.

“This lends further weight to the SVS practice guidelines from 2009, and can hopefully be used to push for more widespread adoption of screening in patients—both male and female—with a positive first-degree-relative family history, even in the absence of a history of smoking.”