A dedicated session at the 2023 VEITHsymposium (Nov. 14–18) in New York City aimed to unpack the ways in which clinical practice and attitudes in the field of chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) have changed since the BEST-CLI trial was published back in November 2022.

The trial’s principal investigators (PIs)—Boston-based vascular surgeons Alik Farber, MD, and Matthew Menard, MD, and interventional cardiologist Kenneth Rosenfield, MD, also of Boston—invited a multidisciplinary panel of opinion leaders from both the U.S. and Europe to share their thoughts and highlight some unanswered questions.

‘We don’t cure these people’

First to comment was vascular surgeon Peter Schneider, MD, from the University of California San Francisco in San Francisco. “One thing I think is worth calling out is the change over one year,” he began. Schneider recalled that, during a 2022 VEITHsymposium session on BEST-CLI, “everybody was worried in some way” about what was going to happen next. A year later, however, he pointed out that “that’s melted away completely.” This change in opinion, in Schneider’s view, is testament to the leadership of the three PIs.

Schneider’s main point was that BEST-CLI has contributed to a recognition that CLTI treatment is “much more complicated” than revascularization alone, predicting that the field is “going to become more like cancer treatment.” He continued: “These people have cancer. It was clear to all of us how sick they are, but now it will be clear to a much broader audience”

Vascular surgeon and SVS President Joseph Mills, MD, from Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, expanded on Schneider’s point. “This cancer analogy works really well,” he said. “We don’t cure these people, and what we want to do is try to put them in remission for as long as possible.” Here, Mills advocated the use of endpoints that look at disease-free survival and wound-free period, suggesting they are probably the most useful for assessing long-term outcomes. “We should start looking at what’s better for [patients’] long-term care and not even one- or two-year results, but what happens over the lifespan of that patient,” he said.

Antiproliferative therapy key

Interventional radiologist Robert Lookstein, MD, from Mount Sinai Health System in New York, echoed Schneider’s sentiment that “the discourse [around BEST-CLI] has become more constructive than deconstructive” over the course of the past 12 months, in large part thanks to the trial leadership.

He was keen to stress, however, that it is “obviously concerning” BEST-CLI reached different outcomes to BASIL-2, presented in April 2023. “It should be recognized they’re studying different populations,” he noted. Lookstein also highlighted the fact that there were very few women and underrepresented minorities enrolled in these two trials, urging caution with regard to extrapolating the results to these specific demographics.

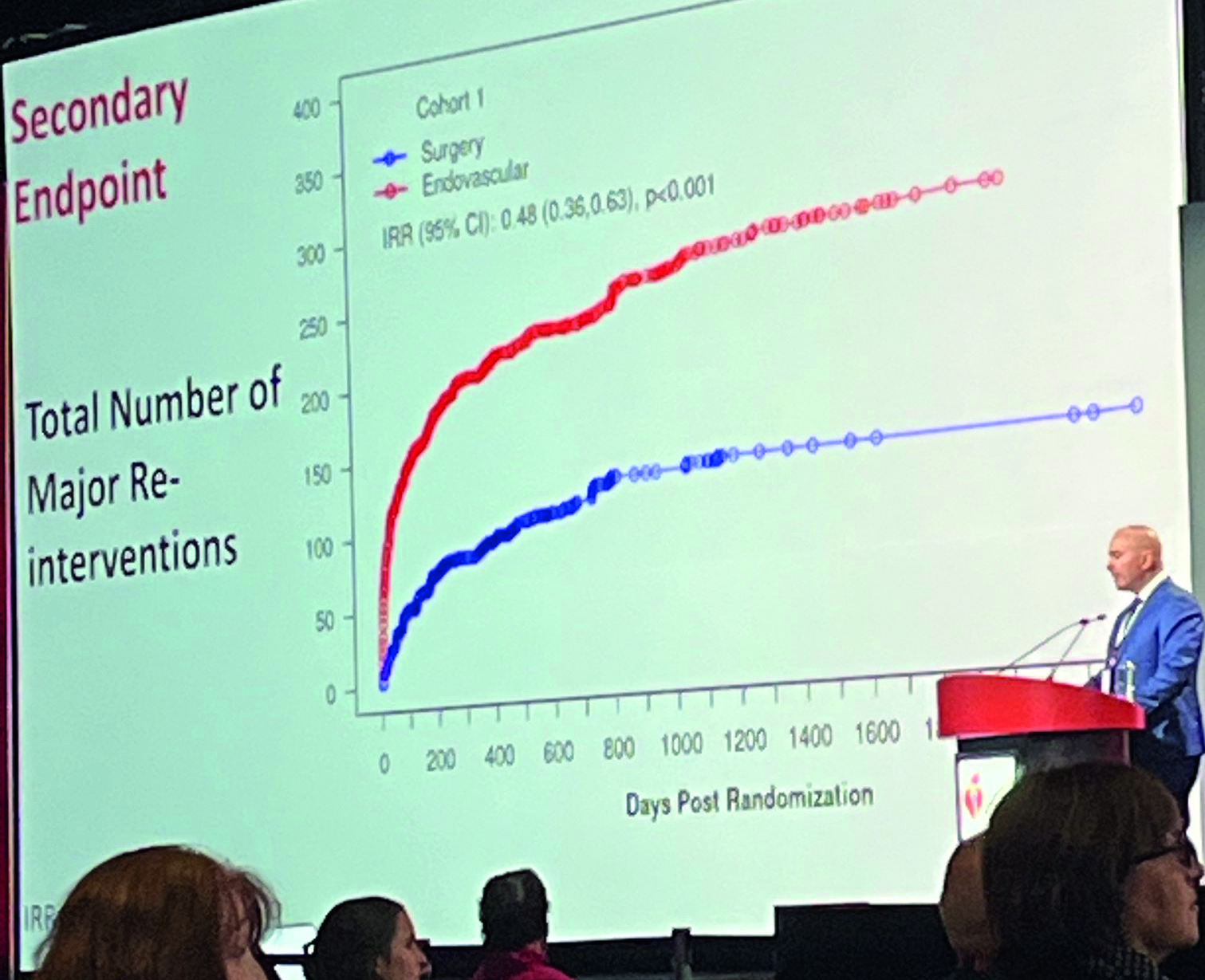

Lookstein’s pointed to the importance of antiproliferative therapy. He referenced a retrospective analysis presented earlier in the session by vascular surgeon Michael Conte, MD, from the University of California San Francisco, that suggested the endovascular arm of BEST-CLI “would probably have better outcomes” had the endovascular protocol been standardized with the level one evidence available on antiproliferative therapy and the infrainguinal circulation. “We have massive amounts of data [showing] that [antiproliferative therapy] is superior to non-antiproliferative therapy,” he stressed, asking why—against this backdrop of evidence— any vascular specialist would withhold this technology from their patients.

Rosenfield, from Massachusetts General Hospital, pointed out that if he were to place a bare metal stent in a coronary vessel, “that would almost be malpractice nowadays.”

Menard, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, also picked up on Lookstein’s point, saying that one of the very important current challenges is that of “how to get the best endo[vascular] and the best surgery out there.”

Lookstein added: “I think it behooves all of us to either lobby the guidelines or to speak out.” He mentioned the “profound” data presented by Conte on the impact of antiproliferative therapy on patency. “I firmly believe drug-coated balloons and stents must be considered the standard of care at this point.”

Put the patient first

Vascular surgeon Elizabeth Genovese, MD, from Penn Medicine in Philadelphia, noted the endovascular-first nature of her clinical expertise, which stemmed from the fact that she had worked for five years in the southeast of the U.S., where her patients had been “very medically complex and often poor surgical candidates.”

Once BEST-CLI was published, Genovese stated that she moved to offering a more “patient-first” approach. Now, she relayed, her practice is framed around the question of which patients fall into the BEST-CLI cohort that does well with bypass first compared to an endovascular-first approach. “These are the patients who not only have good vein, but that tend to be on the healthier spectrum of the patient population; these are the patients that I didn’t necessarily see in the first five years of my practice,” Genovese noted. “But simultaneously, the patients in the open cohort had a fairly high anatomic complexity,” she added, referencing that over 60% of patients had infrapopliteal targets and 51% of the endovascular arm required tibial interventions. “What this study has done for us is made us realize that, in the right patient population, in more complex anatomic patients, bypass first remains still a really good and durable option,” Genovese summarized.

Responding, Rosenfield stressed that “we need to be better about case selection for all of our techniques.”

No more silos

Interventional cardiologist Carlos Mena-Hurtado, MD, from Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, remarked that—for him and his institution—BEST-CLI had been “incredibly important” because “it made us come out of silos and it made us understand […] that CLTI is more than simply just revascularization.” He stressed that, while there is “a lot of work to do,” it is important not to put blame on each other. “I think we need to create the spaces where we can come together and discuss how best to [treat these patients],” he said.

“The single most important thing that I learnt from the trial was the fact that when we had a patient with CLTI come into our facility, we would be forced to look at [the case] together,” Mena-Hurtado added. “We continue that practice up until today, and I think it has made not only our outcomes better, but our patients better.”

‘There’s more work that needs to be done’

Vascular surgeon Maarit Venermo, MD, from Helsinki University Hospital in Helsinki, Finland—who noted that her center was the first site outside the U.S. to join the trial—pointed to the “huge number” of future studies in the works, which she believes will inform decisions around which treatment is best for which subgroups of CLTI patients. “Also, there will be a population who don’t benefit from endo[vascular] or surgery,” she added, stressing the importance of taking this into account when making clinical decisions.

Farber, of Boston Medical Center, also encouraged audience members to look ahead to what is next, stressing that BEST-CLI and BASIL-2 are just the start. “No matter what your views are on [BEST-CLI] or BASIL-2 […], the exciting thing is that we have data coming in this space, which did not have a lot of data [before],” he said. Farber said more work needs to be done, with the “top priority” now to “harmonize” BEST-CLI and BASIL-2 using patient-level data. “It’s an exciting time,” he added.