Aortobifemoral grafting for aortoiliac occlusive disease (AIOD) probably remains “very safe” in the era of endovascular repair, according to the senior author behind a new paper exploring optimal approaches to the often burdensome condition. The research team, led by Jonathan Bath, MD, an associate professor of surgery and the vascular surgery fellowship program director at the University of Missouri in Columbia, Missouri, carried out a comparative analysis of outcomes of endovascular repair and aortobifemoral bypass for AIOD over a five-year period (2016–2021) at their institution, exploring adult patients with Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus Document on Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC) II A-D lesions at their institution.

They presented the results—delivered by Benjamin Liu, BS—at the 2022 annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society (MVSS), which was held in Grand Rapids, Michigan (Sept. 15–17).

The researchers established equivalent outcomes between those treated with both aortobifemoral bypass grafting and unibody endografts (UBEs) in terms of such occurrences as stroke, major adverse cardiac events (MACE) and myocardial infarction (MI). They also reported mid-term outcomes for patency and survival that were similar across the two treatment modalities. The team further found that the best option for TASC C and D lesions—those deemed most complex—remains unclear.

“The thrust of this is that surgeons have been doing aortobifemoral bypass since the 1950s and 60s, and it is well enshrined in vascular surgery as a great option for many patients,” Bath explained in an interview with Vascular Specialist ahead of the MVSS meeting.

“However, we’ve obviously had this endovascular evolution. It is not an entirely new topic but the series have been small, so we don’t have a—collectively—large amount of data to guide us as to which therapy is more appropriate.”

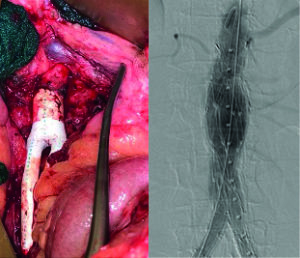

He continued: “We’ve looked at our institutional experience, which, again, is relatively small and modest compared to many, but it has decent, moderate follow-up—36-months in our study. We tried to cohort patients who were similar. If you look at demographics between patients, they really aren’t dissimilar, so we are trying to do an apples-to-apples comparison. We are also going to perform a subgroup analysis on the TASC C and D lesions, the more complex lesions. That was a significant difference between studies: Most of the unibody endografts, or UBEs—the Endologix device—were more TASC A and B patients, with fewer TASC C and D lesions, when compared to the aortobifemoral bypass graft. Obviously, this is a retrospective study; we certainly didn’t randomize these patients. This is operator preference.”

The study included 133 patients who had complete data, 82 of whom had AIOD only. Twenty one of these patients were treated with a UBE (26%), while 61 underwent aortobifemoral bypass grafting (74%). Significant differences in perioperative variables included surgery length (UBE: 213 minutes; bypass: 360), pre- and postoperative ankle-brachial indices (the UBE was lower than the bypass), and sizes of the iliofemoral arteries (larger in the case of the UBE).

The study data also highlighted significant differences in sizes of the iliac, common femoral and superficial femoral arteries between genders—all were smaller in females, Bath notes.

The senior author also described points of interest in terms of study outcomes. “The [patient cohorts] are very similar in terms of the overall outcomes; honestly speaking, there were very few differences in areas such as patency, stroke, MACE and MI in a population that is similar. What that really says, probably, is that aortobifemoral bypass grafting is still very safe, even in the endovascular era.”

There were also specific differences in the size of the arteries in terms of gender, he explained. “That always has implications regarding whether or not an endovascular therapy is going to be superior, or inferior, or the same, versus an open therapy,” Bath said.

“Again, artery size was associated with an overall reintervention risk, so we know the size of the artery does portend a risk of having a reintervention. That might be—in the case of an aortobifemoral bypass graft—that the limb thromboses, and you have to perform a thrombectomy, or, in the case of a unibody endograft, that you may have to extend things, or you may have to perform thrombolysis or some similar procedure in order to maintain patency.”

With all of that being said, Bath finished, “it is true that the aortobifemoral bypass group was more complex and had a greater number of TASC C and D lesions.”

He added: “We really don’t have a great comparison group from the unibody endograft group, so, in this day and age, when there really is a thrust and desire to perform a lot of endovascular therapies, should we be discounting the aortobifemoral bypass graft in patients who are good risk, younger, who may be female with smaller arteries, and who can tolerate an aortobifemoral bypass graft? You would think these TASC C and D lesions would have a greater number of interventions than the TASC A and B [lesions]—i.e. there would a difference between the aortobifemoral bypass group and the UBE—but that did not really play out. So, it really does say that, a) we need a bit more research on the TASC C and D lesions, but b) aortobifemoral grafting is still an excellent option for patients.”

Training implications

The study also recalls the issue of open aortic training volumes amid declining numbers of open abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repairs. During the 2022 Annual Symposium of the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery (SCVS) in Las Vegas earlier this year, Malachi Sheahan III, MD, chair in the division of vascular and endovascular surgery at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, pointed out that aortobifemoral bypass surgery should be part of conversations about trainee involvement in open aortic surgery in discussion over how to tackle shortfalls in the number of such cases tackled by trainees. Bath weighed in on training deficits and the position of aortobifemoral bypasses in the discussion, describing the ongoing hot topic of the last decade as “the deskilling of our specialty with burgeoning endovascular use.”

“We no longer perform as many open aneurysm repairs,” he said, “we no longer perform as many aortobifemoral bypass grafts, and many trainees won’t graduate with the same numbers that we did five and 10 years ago. There has been talk of having open aortic fellowships.” But, like Sheahan, Bath looks toward the bypass further down the vascular tree—not as a panacea but a part of a larger solution. “I would argue that the aortobifemoral bypass graft, although it doesn’t have the same aspects as the aneurysm repair—one cannot say they are comparable— it does teach you many of the principles of open aortic surgery, which is safe exposure and rapid exposure, finding adequate clamp sites; these are all important tenets sewing on an aorta, which oftentimes, people don’t get to do,” he said. “So, I like this operation for that reason. I think we have a bit of a bias, probably, toward performing an aortobifemoral bypass graft in most patients who can tolerate it. And I think it’s good for our trainees.”

Returning to the core of his new study, Bath acknowledged that “there are limitations, there are biases,” saying: “This is a single institution study; surgeons definitely have their biases towards aortobifemoral bypass graft vs. UBE; but I really think this paper demonstrates that aortobifemoral bypass grafting can be performed safely, and has the added benefit of being able to teach residents and trainees how to perform aortic surgery. I think it’s an operation that should remain.”