First retrospective analysis shows comparable outcomes data to those found in PROMISE II pivotal trial, authors report.

The first post-approval multicenter analysis of so-called “no-option” chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) patients treated using a pioneering transcatheter arterialization of the deep veins (TADV) device lays out a set of real-world outcomes that align with those achieved in the PROMISE II pivotal trial of the device, the authors report.

Researchers from Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, New York, MedStar Health in Washington, D.C., and UT Southwestern in Dallas revealed limb salvage rates of 76.1% at six months and 71.7% at one year, respectively, among an 80-patient cohort with a median follow-up of 184 days after TADV (LimFlow, acquired by Inari Medical, now part of Stryker). Furthermore, the study showed survival of 93.1% and 84.7% at six months and one year, respectively. Likewise, the research team reported amputation-free survival rates of 74.2% and 63.6% at the same time points.

The data were revealed during the 2025 annual meeting of the Eastern Vascular Society (EVS) in Nashville (Sept. 4–7) by presenting author Yana Etkin, MD, associate chief of vascular and endovascular surgery in the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell.

Etkin pointed to six-month results from PROMISE II showing a limb salvage rate of 76%, survival of 87.1% and amputation-free survival of 66.1%. “This first real-world, multicenter retrospective study of LimFlow showed outcomes consistent with PROMISE II,” she told those gathered at EVS 2025. “[TADV] achieves favorable outcomes with a high rate of limb salvage up to one year.”

In an interview with Vascular Specialist ahead of presenting the data, Etkin spoke of the device’s role in the fight against diabetes-driven peripheral arterial disease (PAD) across the U.S. “PAD is on rise in the U.S., specifically because of the really high rates of diabetes,” she says. “Every 11th person in our country has diabetes—that is now the no. 1 risk for PAD—and almost 4 million people have PAD. So, the rate of limb loss continues to increase, and probably about 10% of patients who have PAD have what we call ‘no option’ for revascularization.”

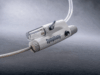

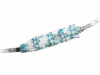

TADV has long been sought after as an alternative means of providing an option for this high-risk CLTI population of patients, Etkin relates. “For years, we have been talking about what to do with these patients, and we’ve tried DVA, where we connect the arteries to the veins, to arterialize the veins, and it has been tried with variable success,” she explains. “Open deep vein arterializations [DVAs] have been described, and percutaneous ones as well, but the percutaneous ones were done randomstance, involving specialists using devices off the shelf, self-made, in very few small series, so not well reported.”

Then along came the LimFlow device, Etkin continues. Approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2023, LimFlow rolled out into the real-world environment off the back of the six-month results’ publication in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). “But the trial is the trial,” Etkin says, “the perfect kind of environment. We started using [LimFlow] in our system when it got approved, and so the idea behind this project was to look at real-world data. Very commonly, after the trials are over, when the devices get to the general population, they don’t perform as well, and then, of course, there is a learning curve.”

With a median follow-up of six months among the 80 patients in the real-world analysis, Etkin points to data showing that of the patients who did not die or lose a limb, stent patency was 70%, with 94% of patients exhibiting either healed or improved wounds. In terms of learning curve of the LimFlow procedure, Etkin can claim 30 of those 80 patients as experience. In that vein, one of the routes to good results involved completing cases together with Northwell vascular surgeon colleague, Jeffrey Silpe, MD, she explains. “The first few cases took a long time, an average of five to six hours,” Etkin says. “But now, after doing these for over a year, we are down to about one-and-a-half to two hours. So, there is definitely a learning curve in probably the first 10 cases.”

She continues, “It is more than just a technical procedure. There is a lot of thought that needs to go into the planning, the intraoperative decision-making. It’s not a straightforward procedure where you have an occluded artery and try to open it up. You’re creating a fistula, and there is a risk that you could steal the blood flow from the native circulation into this fistula, and this fistula is not going to provide enough blood flow for the first six weeks or so because it has to mature. So, you can actually make things worse if you’re not carefully planning and looking at the imaging.”

The procedure is “not going to save everyone,” Etkin says. “This is the first option for these patients who truly have no option.” But, with limb loss associated with “really high mortality,” by saving legs “you’re actually saving people’s lives.”

Work to more fully understand who the right patients are for the TADV procedure continue, Etkin adds. “I think all the results—PROMISE, our results—supports that there is something here that people should really consider including in their treatment algorithm. This is not the first option; this is clearly for when you have exhausted all the options.”