“The path from initial trials to meaningful clinical data will not be easy,” writes Fedor Lurie (Toledo, USA) of new venous valve technologies.

There is an old saying that goes, “As surgeons, we change the anatomy to improve physiology”. Correction of physiological abnormality should, then, result in clinical improvement. The assumptions behind such a three-step logic (anatomy-functionclinical outcome) are frequently challenged, modified and, sometimes, refuted when subjected to scientific examination. Recent developments in the field of chronic venous disease (CVD) make clear the need for such scientific examination of several basic assumptions, one of which is the role of reflux.

Epidemiological studies and clinical observations consistently demonstrate that patients with primary CVD have either deep or superficial venous reflux, or both. Superficial reflux is relatively easy to treat. Multiple clinical trials have shown that ablation leads to clinical improvement. Deep reflux data are less convincing. The introduction of surgical repair for deep venous valves generated several observational studies showing excellent long-term functional and good clinical outcomes.1,2 However, this operation requires the presence of a correctible valve, while most patients with deep reflux have valves damaged by the thrombotic process. Since valvuloplasty was universally performed in patients with terminal venous disease, consensus statements and guidelines restricted recommendations for deep vein reconstruction to patients with venous ulcers.3,4 More than 50 years of clinical experience performing deep reflux correction still did not answer the question of its role in the progression of CVD and the degree to which such correction changes the natural history of this disease process.

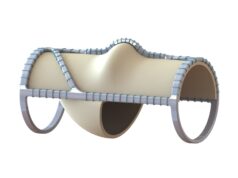

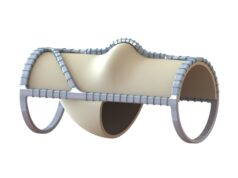

There is a definite need for a practical solution for deep reflux correction. Correction in patients with both primary and secondary CVD—preferably in nonterminal stages of the disease—should answer this question and define the place for such a procedure in clinical practice. Fortunately, several devices are currently in pre-clinical and clinical stages of testing, and the hope is that some solutions will be available soon. However, the path from initial trials to meaningful clinical data will not be easy.

The first challenge is patient selection. Haemodynamics plays an important role in the early stages of venous disease, but has minimal influence in advanced stages.5 The terminal stage is much more a chronic wound process, and correction of haemodynamic abnormalities, although beneficial, has a less clear benefit compared to earlier stages. Limiting the use of deep reflux correction to patients with venous ulcers will not answer the question of whether such a procedure can prevent disease progression. An additional challenge is choosing outcome measures that are related more to haemodynamic correction than to other aspects of ulcer management. The only prospective randomised trial of deep venous valvuloplasty showed that patients with stable disease, or those that remained in the same clinical class for five years before surgery, do not benefit from deep valve repair, while those who progress to more severe disease have a significant clinical improvement.6 This suggests that it is reasonable to use reflux correction procedures in patients in early CVD stages who experience relatively fast progression.

Another challenge is to demonstrate the relationship between improvement in haemodynamics and clinical outcomes. Existing measures of venous haemodynamics and the severity of venous disease are far from perfect and likely to be inadequate for addressing this challenge. The current definition of reflux, although clinically useful, has no meaning in terms of physiological or fluid dynamics. Reverse flow in venous segments is frequently a normal event, even when all valves are competent.7 The time of reversed flow depends on many factors outwith the presence or absence of valvular incompetence. The variability of reflux time measurements is so large that the same patient can be classified as having reflux if tested at different times by the same sonographer using the same procedures and equipment.8 Which parameters of reversed flow are physiologically relevant remain unknown. Suggested candidates range from the volume of blood refluxing back, the flow rate, velocity, vein wall sheer stress and near-wall sheer rate, to a combination of all these measures. Even if the specific factor is defined, ultrasound-based measurements provide information only on one venous segment at a time. The impact of a single segmental reflux correction on the global haemodynamics of extremities is more likely to be clinically relevant and important to assess. Unfortunately, the only existing test for assessing global haemodynamics is plethysmography, which is even less reliable than ultrasound.

The instruments that are used to assess CVD severity were developed by expert consensus (the Venous Clinical Severity Score, or VCSS) or even by a single person (the Villalta score). They reflect more on current perceptions of what constitutes more-or-less severe disease, rather than on scientifically based indicators of disease severity. The exception would be some of the patientreported outcomes—such as VEINES-QOL—that were psychometrically constructed and tested for several aspects of validity.

Like the physiological questions about deep venous valves, the question of appropriate outcome measures of reflux correction is likely to be answered by future clinical experience with valve correction devices.

As practitioners managing patients with venous disease, we are at an exciting juncture—when many questions can be answered and the health of our patients can be improved. All we need is a solution that is practical and efficient at correcting deep venous reflux.

References:

- Kistner RL. Surgical repair of the incompetent femoral vein valve. Arch Surg. 1975 Nov;110(11):1336–42.

- Masuda EM, Kistner RL. Long-term results of venous valve reconstruction: A four- to twenty-one-year follow-up. J Vasc Surg. 1994 Mar;19(3):391–403.

- Lurie F et al. Invasive treatment of deep venous disease. A UIP consensus. Int Angiol. 2010 Jun;29(3):199–204.

- O’Donnell TF Jr et al. Management of venous leg ulcers: Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2014 Aug;60(2 Suppl):3S–59S.

- Welkie JF et al. Hemodynamic deterioration in chronic venous disease. J Vasc Surg. 1992 Nov;16(5):733–40.

- Makarova NP, Lurie F, Hmelniker SM. Does surgical correction of the superficial femoral vein valve change the course of varicose disease? J Vasc Surg. 2001 Feb;33(2):361–8.

- Lurie F. Anatomical Extent of Venous Reflux. Cardiol Ther. 2020 Dec;9(2):215–218.

- Lurie F et al. Multicenter assessment of venous reflux by duplex ultrasound. J Vasc Surg. 2012 Feb;55(2):437–45.

Fedor Lurie is a associate director of the JOBST Vascular Institute in Toldeo, USA.