The following is a combined and revised version of the November and December 2021 editorials on fake news and science denial published in Vascular Specialist. Supplemental information and resources have been added to assist physicians in combating science denial and vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history”

—George Orwell

In March 2019, the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic hit an unprepared New Orleans hard. Hospitalizations and deaths soared unabated. But as the city had done so many times in the past, we came together. We took our medicine. Masks, social distancing, and shutdowns—bitter pills for a place where the economy is based on tourism and the culture is built on community. The city had survived worse. Fires and floods have destroyed the infrastructure here many times over. But like all great places, what makes New Orleans special isn’t the buildings—it’s the people. Resilience and rebirth are in their fabric. So the subsequent outbreaks of COVID-19 seemed self-limited. In Louisiana, we can teach our children the English alphabet from hurricane names and now the Greek alphabet from COVID-19 variants.

The Delta and Omicron waves, though, seem different, darker. The numbers are even greater. On Aug. 21, 2021, one in 1,500 Louisianans are hospitalized with COVID-19. The majority of these patients are unvaccinated. Children are getting sick at an alarming rate. Maybe this time we didn’t all come together. Some of us didn’t take our medicine. Everyone versus the virus started to seem like us versus them. During the first wave, we came together. We buckled down. Physicians retrained to help in the overwhelmed emergency rooms and intensive care units. Some became line teams, putting an endless number of patients on dialysis. We reused our personal protective equipment (PPE), storing our trusty N-95 masks in paper bags for unclear scientific reasons. We took near chemical showers to prevent bringing the virus home to our families. Some of us even learned to recognize that look in our spouse’s eye that said, “I am homeschooling three boys, do not ATTEMPT to complain about your day.” As doctors, though, we did our job. We really did our job.

Physicians need to delicately balance empathy and depersonalization to be effective. If the pendulum swings too far in one direction, our patients suffer, as will we along with them. What happens to our well of empathy when the disease we are facing is entirely preventable? Our actions—which felt heroic at the start of the pandemic—now seem futile. These new deaths were avoidable, so somehow even more tragic. Conspiracy theorists claim the original COVID-19 virus was man-made; well, these endless variants certainly are.

More people in the U.S. died of COVID-19 in the year after the vaccine was approved than in the year before. As of Nov. 30, 2021, 59% of Americans are fully vaccinated. We are 60th in the world. It is a public health catastrophe that was almost entirely preventable. Too often, science and medicine have become matters of opinion, of personal belief. There are solutions to this infodemic, but not all are intuitive.

The truth hurts, but the lies are killing us.

“Tyranny of Doctorcraft!!! Do not be alarmed by the small-pox. Vaccination does cause loathsome and often fatal diseases”

—Excerpts from anti-vaccination pamphlet authored by Alexander M. Ross, MD, in 1885

Science denial is nothing new. We have seen it from the tobacco industry, fossil fuel companies, and even electronic health record (EHR) vendors. Their stance is easy to understand. Create doubt and block consensus. When “the jury is still out,” profit follows. What about science denial that serves no apparent benefit? What about when it is harmful or even fatal? The rise of misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic has been so widespread that the World Health Organization (WHO) labeled it an “infodemic.” To combat the disinformation, physicians need to lead. In the office, in the community, even on social media. Our medical societies need to unite in this process. The American Medical Association’s own House of Delegates directed their organization to collaborate with other specialty groups to combat public health disinformation. But first, we need to understand where the distortions are coming from and why so many people believe them. And then perhaps the most significant test: How do we convince the doubters?

“Standard gargle, mouthwash, has been proven to kill the coronavirus”

—Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis)

Our society is overrun with pseudoscience. Chiropractors, holistic healers, and herbalists promote dubious benefits. Homeopathy claims efficacy through quantum physics (?!). Colonics provide a strikingly unpleasant example of the trust some will place in fake remedies. Think of the “male enhancement” industry, with regular national TV ads featuring celebrities and retired athletes. These ginkgo biloba delivery agents can’t actually promise any specific results, so they are given pornographic names like Malestrom, Lengthergize and others that can’t be mentioned in a family publication like Vascular Specialist. At the start of the pandemic, much of this pseudoscience seemed quaint or silly, but now thousands are dead.

As information gains new pathways, so does misinformation. Fake news is as old as the news itself. Thomas Jefferson once lamented: “Nothing can be believed which is seen in a newspaper. Truth itself becomes suspicious being put into that polluted vehicle.” Jefferson didn’t have to look too far for evidence. Co-Founding Father Benjamin Franklin would frequently write fabricated accounts of murderous Indians working with the British troops. Fake news has always been profitable. In 1835, The New York Sun published a popular series about an alien civilization on the Moon. More recently, journalist Craig Silverman discovered that 140 popular fake news sites all emanated from a small city in Macedonia. Here, a bunch of teenagers were getting rich publishing stories with headlines like “Obama’s Ex-Boyfriend Reveals Shocking Truth That He Wants To Hide From America.”

Traditional media coverage can be skewed even while factual. Think of the focus on anti-maskers and anti-vaxers, even though both healthcare measures have broad support among the population. While the most shared story on Facebook from January to March 2021 concerned whether the vaccine had led to the death of a single physician, more than 3,600 healthcare workers died of COVID-19 during the first year of the pandemic. The press seems especially interested where vaccines fail. Think about how often we learn precisely how ineffective the annual influenza vaccine is, versus how many lives it saves. Of course, fake news can’t spread without an audience. In 1620, Francis Bacon wrote that one of the main barriers to learning the truth was that humans are more likely to believe facts that fit our preconceived notions—a psychological phenomenon we now refer to as confirmation bias. As social groups form and need to feed their preconceived notions, an ecosystem develops to provide this material for profit.

Social beasts

It is often said that humans are social animals. So much so that those who eschew community are labeled with a psychiatric diagnosis (Avoidant Personality Disorder, ICD- 9 301.82). But the need for a group can be pathologic as well. Humans fear social death more than actual death. Shame and embarrassment are two of the most powerful emotions. Suicide bombers, the tragedy at Jonestown, and the Japanese tradition of seppuku are just some examples of individuals choosing physical death over social.

Our communal groups are defined more than ever by social media. Former Facebook manager Tim Kendall testified to Congress that his company “took a page from Big Tobacco’s playbook, working to make our offering addictive from the outset.” He stated that they used the term engagement as a euphemism for the addictive properties of the medium. “The social media services that I and others have built over the past 15 years have served to tear people apart with alarming speed and intensity.” While tearing some apart, social media can also build powerful social groups. So strong are these connections that their members would rather risk death than expulsion.

For some groups, vaccine hesitancy is ingrained. In Native and African Americans, we reap the consequences of our historical sins. Other groups argue that mask and vaccine mandates are threats to “American Freedom”—a claim also used by the tobacco companies against government regulation of their product. So while Patrick Henry exclaimed, “Give me liberty, or give me death!” in 1775, in 2021, they can come as a package deal.

“Let us tell the American people—smokers and non-smokers—that the real issue is freedom of choice. Once the government can control our smoking behavior it can turn the thumbscrews and control other behavior as well”

—Statement of H.R. Kornegay, President, The Tobacco Institute, at the 19th Annual Meeting of the Tobacco Growers Information Committee, Oct. 14, 1977

Indeed, once the pandemic became political, it seemed that we were doomed. Research from the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland, by Stephanie Preston et al demonstrated that individuals are more likely to believe a fake news story if they have personal experience with the subject matter or if the report confirms one of their preconceived opinions. Stories that uncover a “hidden problem” or use numeric graphs are particularly effective. The researchers also found that emotional intelligence was protective. This is a key finding because emotional intelligence can be learned.

One simple trick can tone your abs and identify fake news!

Clear communication and instructions are a cornerstone of public health, but as the battle over the pandemic became political, the waters were muddied. One official who kept a sound, consistent message was Jennifer Avegno, MD, director of the New Orleans Health Department. Folksy at times, “Wash your hands like you just ate crawfish and you need to take your contacts out,” but never failing to keep a coherent dialog. “People who continue to refuse to take the lifesaving COVID vaccine are now also putting the entire community in jeopardy.” Avegno’s efforts led to a higher than the national average vaccination rate in New Orleans. We also became the first city in the U.S. with a proof-of-vaccination or negative COVID-19 test requirement for indoor bars and restaurants.

When I asked Avegno about techniques for reaching the vaccine-hesitant, she told me, “It really depends on why they’re hesitant. Some people just want to talk to a trusted medical professional who will answer their concerns calmly and without judgment. Others need myths they’ve read on the internet debunked, though that’s really hard to do. I think the majority of people who are left unvaccinated now are afraid but don’t even know why, or are so far down a political rabbit hole that there’s little you can say to change their minds.”

In its quixotic quest for objectivity, the mainstream media often confuses the public with “both sides” reporting. So while 97% of climate scientists believe in anthropogenic climate change, only 55% of the U.S. adult population are aware that consensus has been achieved. It is common practice for the media to deliver the opinions of dissenting scientists and physicians as if they were experts, even if their expertise is in another field. Mark McDonald, MD, a consultant to Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, was quoted as saying ivermectin was an “effective, safe, inexpensive treatment” for COVID-19. McDonald is a child psychiatrist. Scott Atlas, MD, was an advisor to the president of the United States, faculty at Stanford, and a fellow at the Hoover Institution.

In April 2020, Atlas said: “We can allow a lot of people to get infected. Those who are not at risk to die or have a serious hospital-requiring illness, we should be fine with letting them get infected, generating immunity on their own, and the more immunity in the community, the better we can eradicate the threat of the virus.” Atlas has no training in infectious disease; his expertise is in magnetic resonance imaging. In fact, his lack of relevant knowledge and experience was so egregious, it was called out by dozens of his former Stanford colleagues as well as Richard Baron, MD, the president and CEO of the American Board of Internal Medicine.

Understanding science

In searching for dissenting opinions, the media often amplifies the voices of the uniformed. Some call it the death of expertise. Much like the one-out-of-five dentists who does not recommend sugarless gum for their patients who chew gum, contrarians can always be found. In my own household, there is an extremely vocal faction that believes Squid Game is appropriate viewing for 12- and 9-year-olds. Fortunately, since this faction is comprised solely of 12- and 9-year-olds, they receive very little publicity.

“You are not a horse. You are not a cow. Seriously, y’all. Stop it”

—8/21/21 Tweet from FDA regarding Ivermectin use

Too often, the media portray science in absolutes, as offering proof. But math is based on proof; scientists continually collect evidence and refine hypotheses. As time goes on, science improves. While we initially hypothesized that the airborne transmission of COVID-19 was unlikely, subsequent evidence contradicted this belief. Therefore the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued new guidance, and our knowledge evolved. As reported in the media, however, this seemed scattershot and led to an erosion of confidence in science.

Fake news sources have flourished as traditional vehicles fail. Recognizing misleading or false stories is a skill that can be learned, but the tell-tale signs may be more subtle than a generous offer from a foreign monarch. Clickbait often proposes “One simple trick” or something “You won’t believe.” Here’s some fun, generate your own clickbait:

- Start with some digits

- Add a gerund (a continuous form of a verb)

- And then some superlative adjectives like cutest, best, and most unbelievable.

Here’s mine: 23 reasons why reading Vascular Specialist will give you the hottest body! OK, your mileage may vary, but by learning how to create fake news, you also learn to recognize it. False stories arise too quickly and spread too far to debunk in real-time. So psychologists at the University of Cambridge came up with a way to pre-bunk them. They developed an online game called Bad News. In it, the user creates a fake news site and learns the six different techniques commonly employed: impersonation, emotional exploitation, polarization, conspiracy, discredit, and trolling. In a controlled trial, the researchers found that individuals who played the game demonstrated a significant increase in their ability to detect fake news items.

Since over 40% of U.S. adults report getting their news from Facebook, instilling emotional intelligence in our population is imperative to mitigate the fallacies of fake news. One such program, already in schools, is called social-emotional learning (SEL). SEL curricula emphasize critical thinking, emotion management, conflict resolution, decision-making, and teamwork. A 2011 meta-analysis of 213 SEL programs comprising over 270,000 students demonstrated an increase in academic performance and a decrease in adverse neurologic symptoms such as anxiety and depression. The concept of SEL is not new. Benjamin Franklin created the first system in the 1700s. For decades, these programs have existed in all 50 states with widespread bipartisan support. Recently, however, organizations such as Parents Defending Education have tried to turn them into political footballs. Taking issue with standards such as “I can make ethical decisions about when and how to take a stand against bias and injustice in my everyday life or community,” the group has accused SEL programs of being vehicles for social justice activism. By politicizing SEL programs, these advocacy groups threaten our best defense against the rising wave of anti-science disinformation campaigns.

Psychologists have demonstrated that the actions of elite cues and advocacy groups affect the gap between scientific and public consensus on many issues. In 1956, Elvis Presley was publicly inoculated with Salk’s polio vaccine on the set of the Ed Sullivan Show. At that time, the vaccination rate among American teens was 0.6%. In the next six months, 80% of US teens would follow his elite cue and join Elvis among the vaccinated. Today, perhaps no one has the cultural reach of Elvis, but we need to find influencers who can push public health measures and create safe social norms in this pandemic. This is why it was a big deal for Louisiana Republican Rep. Steve Scalise to endorse the vaccine publicly; he serves as an elite cue to many conservatives. If nothing else, we need to counter the overhyped media coverage of vaccine skepticism among certain NFL players, and past and present celebrities (say it ain’t so Busta Rhymes!).

When contemplating how to approach my vaccine-hesitant patients, I considered the almost automatic method in which they are delivered in our pediatrician’s office. Truth be told, I used to think my kids got vaccines essentially every visit. The reality was my wife maintained the vaccination schedules imprinted in her memory with Terminator-like accuracy. When the visit calls for a shot, she becomes “busy,” and I step in. This statistical improbability occurred suddenly to my youngest on a drive to the doctor’s office one afternoon. The kids were in the joyous merriment reserved for Christmas, Disney trips, and days they get to leave school early. Suddenly Luke looked up and said, “Wait a minute, why is DADDY driving us to the doctor?” Dread quickly replaced the festive atmosphere of the back seat of my car. Someone, or (oh God), someones were getting the jab. Think about how a pediatrician’s office conducts this process. The doctor doesn’t say, “It looks like Luke has some vaccine hesitancy. Perhaps he would like to hear me debunk Andrew Wakefield’s 1998 Lancet article, which falsely linked the MMR vaccine to autism?” Instead, vaccinations are treated as the social norm. Presumptive language is employed, “Today, Luke is getting his polio and varicella vaccines.”

As physicians, we can help our vaccine-hesitant patients, friends, and family members, but, too often, we use the wrong technique. Doctors frequently engage in a method of debate called topic rebuttal. This is how we discuss and deliberate papers with our peers at scientific meetings. Topic rebuttal is conducted through fact-based counterarguments. This process, though, is only effective in good faith arguments where both sides are open to learning. Lecturing, shaming and ostracizing are also wildly ineffective methods for changing firmly held opinions, usually only serving to entrench your subject further. The fake news complex is well developed and (ironically) very scientific in its approach. Most physicians have not learned useful modes of persuasion. Our attempts often backfire.

Establishing trust

In 350 B.C., Aristotle identified the three rhetorical appeals, Logos (logic), Ethos (credibility) and Pathos (emotion). Aristotle described Pathos as almost a cheat code, effective for overruling reason and logic. Most science deniers don’t necessarily lack information, but they almost always lack trust. To override the emotional connection to their beliefs, we must employ patience and empathy.

“It really had a lot to do with what we thought people would be able to tolerate”

—CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky on why the isolation period was shortened to five days

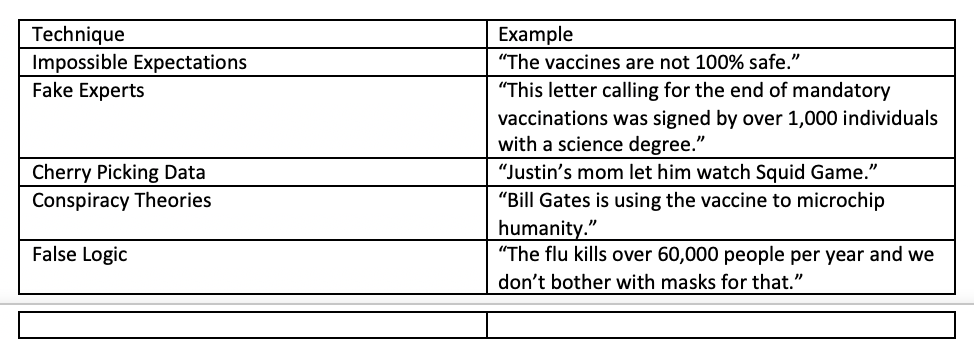

Motivational interviewing is a collaborative, goal-oriented style of communication that has even shown efficacy in one of the most challenging clinical scenarios— physical addiction. When using this technique with the vaccine hesitant, it is essential not to ask why they don’t want the vaccine. That only reinforces their negative feelings. It is better to start with, “On a scale of one to 10, how motivated are you to vaccinate?” If they answer anything other than one, focus the discussion on why they didn’t pick a lower number. This highlights their positive feelings towards the vaccine. The conversation can then be guided by technique rebuttal in which you discuss the standard methods science deniers use to mislead. These commonly include cherry-picking evidence, creating impossible expectations, conspiracy theories, false logic, and fake experts. Reviewing these practices also serves to indoctrinate against further susceptibility to bogus claims. Another key component of technique rebuttal is non-judgmental empathetic listening. The goal is to find your subject’s reasons for hesitancy and bounce them out of a rationalization loop. People who answer one on the motivation scale are in a precontemplation state. Thankfully, this is relatively rare. In studies of parents who oppose childhood immunizations, only 3% were in a precontemplation state.

There are many reasons why someone might not be open to persuasion. Feeling threatened or hopeless are the most common. An interesting method for communicating with people in a precontemplation state is Street Epistemology. The goal of this process is not to change the other person’s mind entirely but to shift their confidence in their belief. Here is a simplified version of the method:

- Build rapport (Ethos)

- Identify the claim your subject is making

- Confirm to them that you understand the claim

- Clarify the terms your subject is using (e.g., mind control, politics, microchip)

- Identify their confidence level in their claim

- Identify your subject’s methods for arriving at their confidence level

- Ask questions to determine if their techniques and sources are sound

Whatever system of persuasion you employ, the goal is to open your subject to an ambivalent position—one where a good faith discussion can be had. Remember, people in certain groups not only don’t care about your approval, they actively don’t want it. Consequently, it is easier to convince some individuals to get the vaccine than wear a mask. A vaccine can be obtained in secret, while wearing a mask can lead to ostracization by their social group.

Consider your faith in the vaccines. Is it based on reading every page of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reports? More likely, you believe because the people you have confidence in—people like you—believe. It is improbable you can convince the vaccine hesitant to trust these same people. But with effort and the proper approach, you might be able to get them to trust you.

“There is a certain movement to insist that now everyone must be vaccinated against the coronavirus COVID-19, and even that a kind of microchip needs to be placed under the skin of every person, so that at any moment, he or she can be controlled regarding health and regarding other matters, which we can only imagine as a possible object of control by the state”

—Catholic Cardinal Raymond Burke

References

- Preston S, Anderson A, Robertson DJ, Shephard MP, Huhe N. Detecting fake news on Facebook: The role of emotional intelligence. PLoS One. 2021 Mar 11;16(3):e0246757

- Fleming N. Coronavirus misinformation, and how scientists can help to fight it. Nature. 2020 Jul;583(7814):155–156.

- Caulfield T. Pseudoscience and COVID-19—we’ve had enough already. Nature. 2020 Apr 27.

- https://www.niemanlab.org/2019/06/yes-its-worth-arguing-with-science-deniers-and-here-are-some-techniques-you-can-use/

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/to-understand-how-science-denial-works-look-to-history/

- https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/05/20/opinion/covid-19-vaccine-chatbot.html

- https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/nov/22/factitious-taradiddle-dictionary-real-history-fake-news

- https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-42724320

- https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/12/fake-news-history-long-violent-214535/

- https://www.americanpurpose.com/articles/a-short-history-of-fake-news/

- Preston S, Anderson A, Robertson DJ, Shephard MP, Huhe N (2021) Detecting fake news on Facebook: The role of emotional intelligence. PLoS ONE 16(3): e0246757. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246757

- Lewandowsky S, Pilditch TD, Madsen JK, Oreskes N, Risbey JS. Influence and seepage: An evidence-resistant minority can affect public opinion and scientific belief formation. Cognition, Volume 188, 2019, Pages 124–139

- https://popular.info/p/the-new-bugaboo

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-elvis-got-americans-to-accept-the-polio-vaccine/

- Fackler A. When science denial meets epistemic understanding. Sci & Educ 30, 445–461 (2021)

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-02152-y

- https://www.niemanlab.org/2019/06/yes-its-worth-arguing-with-science-deniers-and-here-are-some-techniques-you-can-use/

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/to-understand-how-science-denial-works-look-to-history/

- https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/05/20/opinion/covid-19-vaccine-chatbot.html

Malachi Sheahan III, MD, is the Claude C. Craighead Jr. professor and chair in the division of vascular and endovascular surgery at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans. He is medical editor of Vascular Specialist.